Before I dive in, I wanted to share something about my JTBD Masterclass. It’s not just a comprehensive course (with prompts) for eliminating JTBD interviews. You gain access to a community full of additional courses and toolkits. And this is growing. Just wait until you see the next one (I mean 6)!

Introduction: The Whiteboard Was a Masterpiece of Failure

The post-mortem was a quiet affair. Six months earlier, the project kickoff had been electric. The war room was a vibrant collage of colorful sticky notes, elegant journey maps, and beautifully rendered user personas. The team—handpicked, brilliant, and fully committed to the gospel of Design Thinking—had conducted dozens of interviews. They had synthesized, ideated, prototyped, and tested. They had followed the script to the letter. The final prototype they presented to leadership was a masterpiece of user-centric design. It was intuitive. It was beautiful. It was backed by a mountain of qualitative “insights.”

And the product it led to, launched six weeks ago, was a catastrophic failure.

It didn’t just miss its targets; it was met with a profound and resounding market indifference. The users they had so deeply “empathized” with did not care. The problems they had so elegantly “defined” were apparently not problems worth solving. The whiteboard, now a ghost in a decommissioned conference room, had been a masterpiece of failure.

This story is not an exception. It is the rule. This failure was not an accident; it was the inevitable outcome of a process built on a fundamentally flawed premise. The entire corporate world has been taught to worship at the altar of “human-centered design,” a methodology that, in practice, is profoundly unscientific. It is a form of theater, an elaborate ritual that feels productive but is built on the shifting sands of human opinion, cognitive bias, and flawed interpretation.

This manifesto will not just critique that premise. It will dismantle it from first principles and provide a comprehensive, step-by-step, and operationally rigorous alternative. This is a new science of innovation, one that is rooted in objective truth, logical deduction, and the strategic application of artificial intelligence. It’s time to move from the art of guessing to the engineering of value. It’s time to erase the whiteboard and begin with a blank sheet of paper and the laws of physics.

The Original Sin: Why “Empathy” Is a Strategic Trap

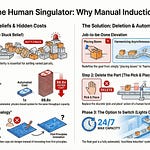

The original sin of modern innovation is committed in the very first step of the process. The directive to “Empathize,” to “talk to your users,” is presented as the foundational act of wisdom. In reality, it is the foundational act of folly. It sends teams to gather data from a poisoned well, ensuring that every subsequent step of the process is tainted. To build a truly resilient innovation practice, we must first have the intellectual courage to deconstruct why this starting point is so catastrophically wrong.

The Deconstruction of the User Persona

The primary tool of the “Empathize” phase is the User Persona. This artifact, often beautifully designed and presented with a catchy name like “Suburban Sarah” or “Millennial Mike,” is a fictional character created to represent a target user type. It includes demographic data, psychographic traits, goals, and frustrations. It is also a complete statistical and strategic fiction.

The Statistical Fallacy: Personas are an exercise in the “flaw of averages.” They take data from multiple individuals and average them into a composite that represents no one. If you have one user who eats a steak for dinner and another who eats a salad, your persona, “Balanced Bob,” does not eat a steak-salad hybrid. He simply becomes an abstraction, a ghost in the machine. Real human beings are not averages; they are specific individuals in specific contexts. The most interesting opportunities for innovation almost always lie in the edge cases, the outliers, the non-average behaviors that a persona, by its very nature, is designed to sand away.

Correlation vs. Causation (A Deep Dive): The data used to build personas—age, location, income, hobbies, a preference for a certain brand of coffee—are, at best, weak correlations. They do not cause behavior. A 35-year-old urban professional who enjoys yoga does not buy a specific project management software because of those attributes. She buys it because she is struggling to get a specific Job-to-be-Done, and she has concluded that this particular solution is the best one to hire for the task. Thousands of other people will fit her exact demographic and psychographic profile and make a completely different choice, because their struggle, their Job, is different.

Consider the spectacular failure of the Juicero press. The persona was perfect: a health-conscious, high-income, tech-savvy urbanite concerned with wellness and convenience. Juicero built a beautiful, $400 machine precisely for this persona. The problem was that the persona didn’t cause the purchase. The underlying Job was “get a healthy, fresh glass of juice,” and the constraints were time and effort. The existing solution—buying a bottle of cold-pressed juice—was far better at getting the Job done within those constraints than a ludicrously expensive machine that squeezed pre-packaged pulp. The persona was a perfect correlation, but it was causally irrelevant.

The Illusion of Understanding: The most insidious aspect of personas is that they give teams a false sense of confidence. They create an intellectual shortcut, allowing a team to say, “What would Sarah do?” instead of engaging with the much harder work of analyzing the fundamental structure of the problem. The persona becomes a substitute for rigorous thought, a mascot for a set of unexamined assumptions.

The Unreliability of the Witness: Cognitive Biases in User Research

If the persona is a flawed artifact, the user interview is a flawed process for gathering the data to build it. A conversation with a customer is not a clean transfer of data. It is a complex psychological interaction, riddled with cognitive biases on both sides that systematically corrupt the information being exchanged.

Anchoring Bias: The user’s perspective is almost always “anchored” to the products and solutions they already use. If you ask a user of Microsoft Word how they would improve their document creation process, they will describe features for Microsoft Word. They are cognitively incapable of describing a solution like Notion or Google Docs, because their entire frame of reference is anchored to the familiar.

The Say-Do Gap: What people say in an interview and what they do in real life are often radically different. A user might say they value privacy and data security above all else, but their actual behavior shows them consistently choosing convenience over security by using simple, recycled passwords. Interview data is data about aspirations and self-perception, not about actual behavior.

The Framing Effect: The way a question is framed will dramatically alter the answer. Asking “What do you find frustrating about this process?” will yield a list of complaints. Asking “Walk me through how you accomplished this task successfully last time” will yield a story of workarounds and successes. The researcher, often unintentionally, frames questions to support their pre-existing hypotheses.

Confirmation Bias: The interviewer is not an objective scientist. They are a human being with a vested interest in their project succeeding. They will subconsciously listen for and give more weight to statements that confirm their existing beliefs (”I knew this was a problem!”) while dismissing or ignoring data that contradicts them (”That user must be an outlier.”).

The Availability Heuristic: Users will disproportionately recall and emphasize recent or emotionally vivid experiences. A minor bug that frustrated them yesterday will be presented as a massive, persistent problem, while a seamless experience from last week will be completely forgotten. The interview does not capture a balanced view of their experience; it captures a snapshot of their most recent emotional state.

To believe that you can conduct a handful of these deeply flawed conversations and emerge with anything resembling objective “truth” is an act of profound self-deception.

The Sandbox of Existing Solutions

The cumulative effect of these flaws is that you end up playing in the sandbox defined by existing solutions. Your “empathy” is constrained by the world as it is, not as it could be. The language your customers use is the language of features, buttons, and workflows given to them by the incumbent products. They can’t articulate a need for something that they have no language for.

No user of a horse and buggy ever articulated the need for a fuel-injection system, an independent suspension, or a catalytic converter. They could only articulate a need for a “faster horse” or a “more comfortable buggy.” They were trapped in the sandbox of their current solution.

Design Thinking, by starting with these users, voluntarily locks itself inside that same sandbox. It becomes a methodology for optimizing the horse-drawn carriage—making it a little faster, a little more comfortable, adding a nicer seat cushion. But it will never, ever lead you to invent the automobile. Breakthrough innovation does not come from studying the sandbox. It comes from understanding the fundamental principles of transportation and then creating an entirely new sandbox.

A Job-to-be-Done: A Theory of Functional Reality

To escape the sandbox, we must replace the flawed foundation of empathy with a foundation of rigorous, scientific truth. This requires a precise and non-negotiable definition of our core unit of analysis: the Job-to-be-Done. The term has been widely popularized, but its common interpretation is the primary reason that most JTBD projects fail. It’s time to correct the record.

A Direct Refutation of the Popular Definition

The most common definition of a Job-to-be-Done, stemming from the brilliant work of Clayton Christensen on Disruptive Innovation, is “the progress an individual is trying to make in a given circumstance.”

While this definition was immensely valuable for framing the theory of disruption, it is a dangerous and misleading oversimplification if your goal is foundational innovation. It contains two critical flaws that inevitably lead teams back to the world of storytelling and subjectivity.

The Flaw of “Progress”: “Progress” is a narrative concept. It is subjective, emotional, and dependent on the individual’s personal story. It invites the innovator to become a storyteller, to craft a narrative about the user’s journey. This feels good—it feels “human-centered”—but it is not engineering. It is a form of marketing, of trying to understand the user’s aspirations. But aspirations are not a stable foundation upon which to build a product. A person’s desire for “progress” can change daily. The functional reality of a task does not.

The Flaw of “Circumstance”: Conflating the Job with the “circumstance” in which it is performed is a catastrophic error. It makes it impossible to create a stable, objective model of the core task. If the Job of “passing the time on a commute” is different from “passing the time while waiting for a friend,” then you have an infinite number of unique “Jobs.” This leads to a fractal explosion of complexity and forces the team to create endless “micro-personas” for each circumstance. You end up back in the world of subjective interpretation, trying to decide which circumstance matters most.

This popular definition is a heuristic, not a theory. It is a useful lens for looking at market disruption, but it is not a tool for engineering new value from the ground up.

The First-Principles Definition of a Job

We must replace the heuristic with a theory. A Job-to-be-Done, from a first-principles perspective, is a core, solution-agnostic, and stable functional process.

It is a system. It has inputs, a process for transforming those inputs, and desired outputs. It is a functional map of what objectively needs to be accomplished, completely independent of the person doing it or the tools they are using.

Let’s break down its key attributes:

Solution-Agnostic: This is the most critical attribute. The Job is not defined by the solution.

The Job is: “Create a visual record of a moment.”

The Solutions are: A cave painting, an oil portrait, a film camera, a DSLR, a smartphone.

The Job is: “Amplify a musical performance for a large audience.”

The Solutions are: A Greek amphitheater’s acoustics, a megaphone, a vacuum-tube PA system, a modern digital line array. To innovate, you must deconstruct the Job, not the current solution.

Stable Over Time: Because the Job is solution-agnostic, it is incredibly stable. The Job of “transmitting critical information securely over a long distance” has existed for millennia. The solutions have evolved from marathon runners to signal fires to the telegraph to encrypted digital messages, but the fundamental Job Map—define the message, encode it, transmit it, receive it, decode it—has remained remarkably constant. This stability is what makes it a reliable target for innovation.

Objectively Verifiable: The steps in a well-defined Job Map can be observed and agreed upon, independent of who performs them. The steps to “prepare a sterile surgical field” or “compile source code into an executable file” are objective processes. There can be better or worse ways to execute them, but the core functional steps are not a matter of opinion. They are a matter of functional reality.

The Anatomy of a Constraint: The True Source of Opportunity

If the Job is the stable, objective process, then where does the messy reality of the user’s world come in? It comes in the form of constraints. A constraint is any factor that forces the execution of the Job to deviate from the perfect, most efficient path.

The Job is the perfect, straight road. The constraint is the boulder in the middle of it. The struggle is the friction between the ideal process (the Job) and the constrained reality of the user’s context. Innovation is the process of systematically identifying and eliminating that friction.

To do this, we need a formal classification of constraints:

User Constraints: These are limitations inherent to the person executing the job.

Lack of Skill: The user doesn’t know the optimal technique.

Cognitive Load: The process requires too much mental effort or memory.

Physical Limitations: The user has dexterity, strength, or sensory challenges.

Access Limitations: The user doesn’t have the necessary permissions or credentials.

Environmental Constraints: These are factors in the user’s context.

Time Pressure: The job must be completed within a limited duration.

Location: The job must be done in a specific, often suboptimal, place (e.g., on a noisy train, in a cramped workspace).

Ambient Conditions: Factors like poor lighting, extreme temperatures, or bad weather interfere with the job.

Technical Constraints: These relate to the tools and systems involved.

Lack of Connectivity: The job requires data, but internet access is unavailable or unreliable.

Incompatible Systems: The tools used for different steps of the job cannot exchange data.

Outdated Hardware: The user is forced to use slow, inefficient, or feature-poor equipment.

Regulatory & Social Constraints: These are external rules or norms.

Legal Requirements: The job must adhere to specific laws or compliance standards (e.g., HIPAA, GDPR).

Social Norms: The user must execute the job in a way that is socially acceptable.

Ethical Considerations: The job involves choices with moral implications.

The great failure of “empathy” is that it mushes all of this together. It sees the user’s frustration but fails to diagnose the root cause. It doesn’t distinguish between a frustration caused by a lack of skill (a user constraint) and one caused by an inefficient tool (a technical constraint). Our new approach demands this precision. We must separate the objective Job from the constraints that impact its execution. Only then can we see the true opportunity for innovation.

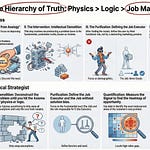

The New Engine: First Principles, AI, and the Objective Job Map

We have established a new foundation: our goal is to understand the objective, functional Job, not the subjective opinions of users. This requires a new engine for discovery and analysis. We must move from the qualitative art of the interview to the rigorous science of deconstruction. This is a three-part process: deconstruct the domain to its core truths, use AI as a logic engine to construct the ideal Job Map, and use that map as an objective benchmark.

A Step-by-Step Guide to First-Principles Deconstruction

The process of innovation begins not in a user’s office, but in a library, a physics textbook, or a legal document. It is an analytical exercise to find the immutable truths—the axioms—of a domain.

Step 1: Defining the Domain. The first step is to precisely define the boundaries of the Job you are analyzing. “To manage money” is too broad. “To pay a bill” is too narrow and solution-specific. A well-defined Job is something like “Allocate capital over time to maximize future well-being.” This is abstract enough to be solution-agnostic but bounded enough to be analyzable.

Step 2: The Art of Identifying Axioms. An axiom is a statement about the domain that is non-negotiably true and cannot be broken down further. It is a fundamental rule of the game. The goal is to find the 5-10 core axioms that govern the domain.

Where to Look: Axioms are not found in customer interviews. They are found in formal systems. For a financial job, you look at the mathematical formulas for compound interest and the legal text of the tax code. For a physical engineering job, you look at the laws of thermodynamics and material science. For a software job, you look at the principles of information theory and computational complexity.

Good vs. Bad Axioms: A bad axiom is an opinion or a best practice (e.g., “A user prefers a simple interface”). A good axiom is a fundamental truth (e.g., “The time value of money dictates that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow”).

Step 3: Building the Causal Chain. Once you have your axioms, you begin to link them together to understand the fundamental logic of the domain. You ask: “Because this axiom is true, what else must also be true?” This process builds a chain of deductive logic that forms the bedrock of your understanding, completely free of any user’s opinion.

The AI as a Deductive Logic Engine: A Look Under the Hood

Historically, building a comprehensive Job Map from these axioms was an incredibly laborious, time-consuming process reserved for a few elite experts. Today, we have a powerful new tool to accelerate this process: Artificial Intelligence.

It is critical to understand the role the AI plays here. It is not a creative partner. We are not asking it to “brainstorm” ideas. We are using a Large Language Model as a deductive logic engine. We provide it with a set of constraints (the axioms) and ask it to perform a task of logical synthesis and process optimization.

The Prompting Process: The input to the AI is highly structured. It might (🤣) look something like this:

“You are a systems engineer. Your task is to create a comprehensive, logically sound, and maximally efficient process map for the Job of ‘Allocate capital over time to maximize future well-being.’ This process must strictly adhere to the following five axioms: [List of Axioms]. The output should be a hierarchical map with no more than five main stages, and each stage should contain a series of discrete, functional steps. The language used must be solution-agnostic.”

Validation and Refinement: The AI’s output is not a final answer. It is a powerful first draft. Human experts then take this AI-generated map and rigorously validate it against the axioms. They look for logical gaps, inconsistencies, or inefficiencies. This human-AI partnership combines the AI’s ability to rapidly process and structure information with the deep domain expertise of the human, resulting in a robust and comprehensive map in a fraction of the time it would have taken a human alone.

The Anatomy of the Objective Job Map

The final output of this process is the Objective Job Map. This is the single most valuable strategic asset an innovation team can possess. Let’s illustrate this with a detailed example: the Job of “Planning and executing a multi-day backpacking trip.”

The Hierarchical Structure:

Main Job: Plan and execute a multi-day backpacking trip.

Phase 1: Define Trip Parameters

Step 1.1: Determine desired outcomes (e.g., solitude, physical challenge, specific destination).

Step 1.2: Identify core constraints (e.g., duration, budget, participant skill level).

Step 1.3: Select geographic region and season.

Phase 2: Plan Route and Logistics

Step 2.1: Research and select a specific trail or route.

Step 2.2: Acquire necessary permits and reservations.

Step 2.3: Create a day-by-day itinerary (mileage, campsites).

Step 2.4: Plan water sources and resupply points.

Step 2.5: Create contingency plans for emergencies.

Phase 3: Prepare Gear and Supplies

Step 3.1: Create a comprehensive gear checklist based on route and weather.

Step 3.2: Inspect and repair existing gear.

Step 3.3: Acquire new or replacement gear.

Step 3.4: Plan a complete food menu.

Step 3.5: Purchase and repackage all food supplies.

Step 3.6: Pack backpack ensuring optimal weight distribution.

Phase 4: Execute the Trip

Step 4.1: Travel to the trailhead.

Step 4.2: Navigate the planned route.

Step 4.3: Execute daily camp routines (setup, cooking, breakdown).

Step 4.4: Monitor weather and trail conditions and adjust plan accordingly.

Step 4.5: Manage physical exertion and health.

Step 4.6: Adhere to Leave No Trace principles.

Phase 5: Conclude the Trip

Step 5.1: Travel from the trailhead.

Step 5.2: Clean and store all gear.

Step 5.3: Share trip records or memories.

The Comprehensive List of Success Metrics: This is where the map becomes truly powerful. For each step, we can define the objective metrics of a perfect outcome. Here is just a small sample of what would be a list of 50-100+ metrics for the full map:

(From Stage 2) Minimize the discrepancy between the planned itinerary and the executed trip to less than 10%.

(From Stage 2) Maximize the probability that all required permits are secured on the first attempt.

(From Stage 3) Minimize the total base weight of the packed backpack while maintaining a safety and comfort score above a defined threshold.

(From Stage 3) Reduce the likelihood of gear failure during the trip to less than 1%.

(From Stage 3) Ensure the total caloric value of packed food is within 5% of the calculated required energy expenditure.

(From Stage 4) Minimize navigational errors to zero deviations from the planned route.

(From Stage 4) Reduce the time required to set up or break down camp to under 30 minutes.

(From Stage 4) Maximize the accuracy of weather predictions against actual conditions.

(From Stage 5) Minimize the time from trip end to having all gear cleaned and properly stored.

This level of detail is not obsessive. It is essential. This is our blueprint for “perfect.” It is our objective reality, and now, for the first time, we have a tool to measure the real world against it.

The New Playbook: From Objective Maps to Market Domination

The Objective Job Map is not an academic exercise. It is a weapon. It provides a clarity that allows an organization to move from reactive guesswork to proactive, strategic innovation. It transforms the entire playbook for how to find opportunities and build solutions.

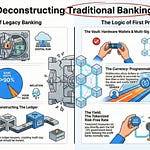

The Tale of Two Teams (Expanded Narrative)

Let’s revisit our two teams, but let’s give them names and voices. Both are tasked with innovating in personal finance for millennials.

Team Empathy, led by Sarah, a passionate Design Thinking advocate. Her team spends a month conducting interviews. In a debrief meeting, she stands before a whiteboard covered in quotes and photos.

“Okay team,” she says, “the key insight is anxiety. Our persona, ‘Freelance Felix,’ feels a constant, low-grade stress about his variable income. He told us, and I quote, ‘I feel like I’m flying blind.’ He’s frustrated by his banking app; it’s just a list of transactions, it doesn’t make him feel in control.”

One of her designers chimes in…

“We saw that too. He wants to feel more confident. It’s an emotional need.”

The result of their work is “Zenith,” a new budgeting app. It has a beautiful, minimalist UI, uses a calming green color palette, and sends encouraging notifications. It re-categorizes spending into “Mindful” and “Impulsive” buckets. It is a masterpiece of empathetic design. It gets rave reviews for its user interface. It fails to gain any meaningful market traction, because it doesn’t actually help Felix make better financial decisions; it just makes him feel momentarily better about making bad ones.

Team Principles, led by David, a former systems engineer. David’s team spends their first month in a closed room with textbooks on economic theory, finance, and tax law (or they leverage AI here as well). Their whiteboard is covered in formulas and logical proofs. David addresses his team…

“Forget the user for a moment. What is the physics of this problem? The Job is ‘Allocate capital to maximize future well-being.’ The axioms are the time value of money, the mathematical relationship between risk and return, and the hard constraints of the tax code. Let’s build the perfect engine first.”

They feed these axioms to their AI engine. The AI returns a 7-stage Job Map for perfect capital allocation. It is a thing of brutal, logical beauty. Only then do they go out into the real world. They don’t conduct “empathy interviews.” They conduct “struggle interviews.” They take the map and ask people…

“Where does your real-world process break down when compared to this perfect model?”

They discover a massive, universal struggle at Stage 3, Step 4: “Accurately price the risk of idiosyncratic, illiquid assets.” Every freelancer, every startup employee, every small business owner has this problem. Their financial future is tied to assets—private equity, future receivables, personal brand value—that have no clear price. No budgeting app on earth can handle this. Their innovation is “Riskfolio,” a tool that uses sophisticated financial modeling to help people price and manage these assets. It’s not as pretty as Zenith, but it solves a massive, painful, and completely unmet need. It creates an entire new category and becomes indispensable to its users.

Quantifying the Struggle: The Missing Link

David’s team had a powerful insight, but how could they prove its market size? This is the final piece of the playbook: using the Objective Job Map to quantitatively measure market opportunity.

This is achieved with a new kind of survey. You do not ask for opinions. You take the Success Metrics from your AI-generated map and you ask a statistically significant group of people within a specific context to rate two things for each metric on a scale of 1 to 10:

Importance: How important is it to you that this outcome is achieved?

Satisfaction: How satisfied are you with your ability to achieve this outcome today, using your current solutions?

The results are then plotted on a chart. The Y-axis is Importance, and the X-axis is Satisfaction. The metrics that fall into the top-left quadrant—High Importance and Low Satisfaction—are your prime opportunities for innovation. They are the biggest, most painful struggles in the market, identified with mathematical certainty. This chart is the ultimate antidote to guesswork. It’s a treasure map showing exactly where the value is buried.

Strategy Beyond the Product

This quantitative map of unmet needs is the ultimate input for corporate strategy. And it allows you to innovate far beyond just building a new product. By using a framework like Doblin’s 10 Types of Innovation, you can see that a single unmet need can be solved in multiple ways.

Unmet Need: “Minimize the upfront cost of acquiring necessary equipment.”

Product Performance Innovation: Make a cheaper version of the equipment. (The obvious, easily copied answer)

Profit Model Innovation: Don’t sell the equipment at all. Lease it. Offer it “as-a-service.” (e.g., Hilti’s tool fleet management)

Service Innovation: Offer a service that helps users get more value out of cheaper equipment through expert training and support.

A competitor can copy a feature. It is incredibly difficult for them to copy a unique Profit Model, combined with an innovative Service, delivered through a novel Channel, all designed to solve the customer’s top three unmet needs with ruthless efficiency. This is how you build a durable, defensible competitive moat.

Conclusion: The Shift from Sociology to Epistemology

The tools of Design Thinking—the persona, the journey map, the empathy interview—are the tools of sociology. They are designed to study people, their cultures, and their feelings. This is a valuable field of study, but it is a soft science. Its findings are qualitative, subjective, and difficult to verify. Building a multi-billion dollar business on a foundation of sociology is like building a skyscraper on a foundation of sand.

The new playbook is a shift to epistemology. Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of knowledge, justification, and rationality. It asks: “What is true, and how can we know it’s true?”

The new role of the innovator is no longer to be a qualitative researcher or a creative genius who has a magical flash of insight. The innovator is an epistemologist who has the discipline to discover the objective truth of a problem. They are a physicist who understands its fundamental axioms and constraints. And they are an engineer who systematically builds a solution to bridge the gap between that objective truth and our messy, constrained reality.

This approach is harder. It requires more rigor. It requires a comfort with abstraction and a willingness to abandon the comforting rituals of the sticky note. But it provides a strategic advantage that is almost unfair. It allows you to see the world with a clarity your competitors cannot fathom. It allows you to make bets based on evidence, not on stories. It allows you to build the future, not just a slightly better version of the present.

Stop asking people what they want. Stop trying to “empathize.” Start with the truth. The immutable, inconvenient, and incredibly powerful truth of the Job-to-be-Done.

What is one “core axiom” from your own industry that is consistently ignored or violated by today’s solutions? Share it in the comments.

Follow me on 𝕏: https://x.com/mikeboysen

If you’re interested in inventing the future as opposed to fiddling around the edges, feel free to contact me. My availability is limited.

Mike Boysen - www.pjtbd.com

De-Risk Your Next Big Idea

Masterclass: Heavily Discounted $67

My Blog: https://jtbd.one

Book an appointment: https://pjtbd.com/book-mike

Join our community: https://pjtbd.com/join