🚨🚨 Please Participate 🚨🚨

I’m doing some innovation research and could use your help. In exchange, I’m happy to offer you FREE access to my JTBD Masterclass and 6 other courses that come with it. It’ll take less than 10 minutes of your time.

This is completely anonymous unless you opt-in for the Masterclass

Click here to participate: https://web.jtbd.one/inno-survey

Introduction: The End of an Era

For the last forty years, you’ve been living inside the same digital house. The furniture has been rearranged, the walls have been repainted, but the fundamental architecture has remained untouched. This house is the graphical user interface (GUI), and its rooms are the applications we’ve been conditioned to live and work in. From the first click of a mouse on a desktop folder to the thousandth tap on a smartphone app, the core metaphor has been the same: you, the user, must navigate a landscape of digital tools, acting as the sole integrator for your own goals.

This model was a revolution. It took computing from the hands of specialists and gave it to the world. But all revolutions eventually become the old guard. The app-centric paradigm, a system that forces you to context-switch between dozens of single-purpose silos, has reached its point of diminishing returns. The friction you feel—the digital clutter, the notification fatigue, the endless copying and pasting between windows—isn’t a personal failing. It’s a systemic one.

We’re drowning in a sea of tools, yet we’re thirstier than ever for progress.

This isn’t an argument for a better version of Windows or a slicker macOS. This is an argument for a complete paradigm shift. The next great leap in personal computing will not come from refining the old model but from replacing it entirely. It requires a fundamental shift in perspective: from a tool-centric model, where you manage apps, to an outcome-centric model, where the system achieves your goals for you.

This is the dawn of the post-app operating system. It’s an OS that doesn’t ask you what tool you want to use, but what you want to accomplish. It’s an OS that measures its success not by how much time you spend with it, but by how much time it saves you.

To build this future, we can’t just iterate. We have to deconstruct the present. In this deep-dive, we’ll explore the five foundational principles that serve as the blueprint for this new, outcome-driven world. These aren’t just theories; they are the architectural pillars for the next generation of personal computing.

The First Principle: Deconstruct the App-Centric Monopoly on Interaction

Before we can build something new, we have to dismantle the assumptions that hold the old world in place. The most powerful way to do this is through First Principles Thinking. Instead of reasoning by analogy (”let’s make it like this, but better”), we’ll break the entire concept of an operating system down to its foundational truths and build up from there.

This isn’t about criticizing the past; it’s about clearing the ground for the future.

A. Preparation: Defining the Problem

First, we need to reframe the problem. A loaded premise would be, “The modern OS is bloated and inefficient.” This assumes a flaw. A neutral reframing gets to the core function. The “job” that you hire an operating system to do isn’t to “run software” or “manage files.” The real, underlying job is to help you achieve successful outcomes with the least amount of effort.

With this job in mind, we can objectively analyze the components of the current system to see if they are the best possible solution for getting that job done.

B. Deconstruction: Identifying the Foundational Assumptions

Now, let’s identify the unwritten rules and inherited assumptions that govern every OS you’ve ever used. For decades, these have been treated as laws of nature, but they are merely design choices that have become calcified over time.

Assumption 1: The “App” is the fundamental unit of interaction. We believe that to perform any digital function—writing a message, checking the weather, booking a flight—we must open a discrete, branded, siloed piece of software called an “application.”

Assumption 2: The user must act as the system integrator. The OS provides a toolbox (the apps), but you are the carpenter. It’s your responsibility to know which tools to use, in what order, and to manually transfer information between them to complete a project.

Assumption 3: The screen is the primary interface. Our interaction model is built around direct manipulation of visual objects on a 2D plane—clicking icons, dragging files, tapping buttons. Your attention is the resource the OS is designed to capture.

Assumption 4: Data ownership is tied to the application silo. Your playlists belong to your music app, your documents belong to your word processor, and your social connections belong to your social media app. Data is trapped within the walls of the application that created it.

C. Validation: Refuting the Assumptions with Foundational Truths

This is where we challenge the dogma. Are these assumptions truly fundamental, or are they just habits we’ve mistaken for principles?

Refuting Assumption 1 (The App is Fundamental): The “app” is an artificial container. You don’t actually want to “use a map app.” You want to get to your destination on time. The app is a means, not the end. The true fundamental unit of interaction isn’t the software; it’s your intent. The job you are trying to get done is the atomic unit. The app is just one, often inefficient, solution for fulfilling that intent. A foundational truth is that technology should be organized around human goals, not software containers.

Refuting Assumption 2 (The User is the Integrator): This assumption is a direct relic of technical limitations from the 1980s. It places an enormous cognitive load on you, forcing you to perform rote, machine-like tasks of context-switching and data transfer. A foundational truth is that computers are exponentially better at orchestrating complex, multi-step processes than humans. The system, not the user, should bear the burden of integration. Your role is to state the goal, not to manage the workflow.

Refuting Assumption 3 (The Screen is Primary): The screen-centric model demands your most valuable asset: your focused attention. But intent can be expressed in far more efficient ways—voice, text, or even passively through learned behavior. A foundational truth is that the most powerful interface is the one that requires the least interaction. The goal is to reduce the time spent managing the machine so more time can be spent living. An ideal OS is ambient, working in the background, rather than demanding to be the center of attention.

Refuting Assumption 4 (Data is Siloed): This is a business model masquerading as a technical necessity. It creates platform lock-in and immense friction for you, the user. A foundational truth is that your data is a reflection of you—your relationships, your memories, your plans. It should be user-centric and portable, accessible to any service you grant permission to, in service of getting your job done, without being held hostage by a specific application.

D. Synthesis: Establishing the New Foundation

By clearing away the debris of these refuted assumptions, we’re left with a set of powerful, foundational truths—our new first principles—from which we can design the post-app operating system.

The OS must be Intent-Driven. The system’s primary input should not be a click on an icon, but the user’s stated goal or desired outcome.

The OS must be the Integrator. The system is responsible for orchestrating all the necessary services, APIs, and information to achieve the user’s intent, eliminating manual workflow management.

The OS must be Ambient. The ideal interface is conversational or even predictive, minimizing the need for direct manipulation and freeing user attention.

The OS must be User-Centric. Data should be controlled by and portable for the user, available to a fluid ecosystem of services that compete based on their ability to get the job done, not on their ability to lock in data.

This new foundation is the bedrock for the remaining four principles. It represents a complete reversal of the current model—from you serving the system to the system serving you.

The Second Principle: Re-center on the User’s “Job to be Done,” Not Their Tasks

The first principle gave us our “why.” This second principle, grounded in the theory of Jobs-to-be-Done (JTBD), gives us our “what.” It provides a new lens for understanding user needs.

JTBD theory is simple but profound: customers don’t buy products; they “hire” them to get a job done. A “job” is a core, solution-agnostic, and stable functional process. It’s not a task; it’s a goal, an objective, a struggle. Jobs are stable over time; the solutions change. This shifts our focus away from the product and its features and onto the user’s underlying goal and the context in which that goal exists.

In the world of operating systems, this means we stop thinking about user tasks and start focusing on the user’s job.

A task is solution-specific and procedural. “Open the calendar app, create a new event, invite attendees, and set a reminder.”

A job is solution-agnostic and aspirational. “Ensure I am fully prepared for my upcoming meeting.”

See the difference? The first is a description of how you wrestle with current tools. The second is the actual outcome you’re trying to achieve. Getting the job done might involve scheduling, but it also involves gathering research documents, communicating with the team, and blocking out focus time. The current app-centric OS only helps you with a fraction of that job, leaving you to be the integrator for the rest.

An outcome-driven OS starts with the job. To do this, we must get precise about defining it. A well-formed “Job Statement” has a specific structure and uses a specific lexicon. The goal is to capture the user’s need in a way that is free from any mention of a current solution.

Bad Job Statement: “The user wants to use a video conferencing app.” (Describes a task with a solution).

Better Job Statement: “The user wants to communicate with their remote team.” (Better, but still vague).

Excellent Job Statement (using JTBD Verb Lexicon): “The user wants to share information and align on decisions with colleagues to advance a project forward with clarity and speed.”

This statement is powerful because it’s rich with opportunity. It contains the core functional job (share information), the desired outcome (advance a project), and the emotional and practical guardrails (with clarity and speed). It gives a designer a clear target to aim for, one that isn’t constrained by the idea of building a “better video conferencing app.”

An OS designed around this principle would stop presenting you with a grid of app icons and start helping you define and execute your jobs. Instead of you opening five different apps to prepare for your meeting, you would simply state your intent to the OS: “Get me ready for my 2 PM project sync.” The OS, understanding the underlying job, would then orchestrate the necessary services to accomplish it—gathering the relevant documents, summarizing recent email chains, setting a focus timer, and ensuring the meeting link is ready when you need it.

The Third Principle: Elevate the User by Raising the Level of Abstraction

Every major leap in computing history has been defined by one thing: raising the level of abstraction. This simply means hiding complexity from the user. We moved from plugging in wires to punch cards, from punch cards to the command line, and from the command line to the GUI. Each step removed a layer of technical burden from the user, making the technology accessible to more people and applicable to more problems.

Punch Cards: You had to understand machine architecture.

Command Line: You had to learn a specific, rigid syntax.

GUI: You had to learn the procedural “language” of clicks, menus, and icons.

The intent-driven, post-app OS is the next logical step in this progression. It’s the highest level of abstraction yet because it hides the complexity of procedure itself.

Think of it like a ladder of cognitive load:

Bottom Rung (High Complexity): The command line. You have to tell the computer what to do and exactly how to do it.

mv /users/me/docs/report.docx /users/me/archive/Middle Rung (Medium Complexity): The GUI. You still have to know the procedure, but the interface is more intuitive. You drag the “report” icon from the “docs” folder to the “archive” folder. You are still manually executing the steps.

Top Rung (Low Complexity): The Intent-based OS. You only have to state your desired outcome. “Archive this report.”

In this new model, you don’t need to know which apps to use or how to use them together. The system abstracts that entire layer of complexity away. Your only job is to communicate your intent. This drastically reduces your cognitive load, freeing up mental energy for higher-level thinking and creative problem-solving—the things humans are best at.

This is the ultimate form of user-centric design. It doesn’t just make the existing steps easier; it eliminates them entirely. The technical challenges are immense, of course. It requires incredibly sophisticated natural language understanding, user context awareness, and service orchestration. But the goal is clear: to create an OS where the user’s interaction is as simple and powerful as a conversation with a world-class assistant.

The Fourth Principle: Build the Engine—Orchestration Through Agentic Layers

If the user’s input is “intent,” what is the engine that translates that intent into a completed outcome? It’s not a single, monolithic AI. A more resilient and scalable model is a layered architecture of cooperative, specialized AI agents. This is the “how” behind the magic.

We can think of this as a four-layer stack:

The Intent Layer: This is the user-facing layer, the “top of the stack.” It’s the conversational interface (text or voice) where you state your goal. Its job is to capture and clarify your intent, asking follow-up questions if the goal is ambiguous (e.g., “When you say ‘plan a trip to Paris,’ are we optimizing for cost, travel time, or experience?”).

The Agent Layer: This is the orchestration layer. Once your intent is clear, a “master agent” or “chief of staff agent” breaks down the high-level goal into a series of smaller tasks. It then delegates these tasks to a team of specialized agents. Think of it like a project manager. You might have a “travel agent,” a “calendar agent,” a “research agent,” and a “communication agent.” Each is an expert in its domain.

The Execution Layer: This is where the work gets done. The specialized agents in the layer above don’t perform the tasks themselves; they access the tools to do so. This layer is composed of APIs, services, and legacy applications. The “travel agent,” for example, would access airline APIs, hotel booking services, and map data to fulfill its delegated task of booking a flight and hotel.

The Outcome Layer: This is the feedback loop. As the execution layer completes tasks, the results are synthesized and presented back to you through the intent layer. This isn’t just a final report; it’s an ongoing process. “I’ve found three flight options that fit your budget. Do you want to review them, or shall I book the one with the best balance of cost and layover time?”

This layered, agentic model is powerful because it’s modular, scalable, and adaptable. You can add new specialist agents or connect to new services in the execution layer without having to redesign the entire system.

Things Working Today That Few Are Doing

This might sound like science fiction, but you can see the primitive ancestors of this model in the market today. Tools like Zapier and IFTTT are rudimentary “user as integrator” platforms that hint at the power of service orchestration. Complex Siri Shortcuts or Google Assistant routines are early forms of intent-driven workflows. These tools are still clunky and require you to do all the setup, but they prove the underlying concept: chaining discrete services together creates value far beyond what any single app can offer.

Novel Concepts for the Future

Now, let’s extrapolate. What does a mature version of this look like?

Proactive, Goal-Seeking Agents: Imagine telling your OS, “Help me get a promotion this year.” The OS could then create a long-term plan, managed by an agent that proactively suggests actions: “Based on your career goals, I recommend taking this online course in data analysis. I’ve found three options and can enroll you.” Or, “You haven’t spoken with your mentor in two months. I’ve drafted a check-in email for you. Should I send it?”

Negotiating Agents: What if your “shopping agent” could negotiate with a retailer’s “sales agent” in real-time to get you the best price, based on your stated budget and preferences? The OS would act as your economic advocate in the digital world.

The End of the Browser: In a world where agents can access and synthesize information from any API or service, the need for you to manually navigate websites in a browser diminishes. The browser becomes a legacy tool, a part of the execution layer that agents use, but that you rarely touch directly (see my article below).

This agentic architecture is the engine of the outcome-driven OS. It’s the system that finally delivers on the promise of the computer as a “bicycle for the mind”—not just a tool you operate, but a partner that helps you achieve your goals.

We will likely see a ladder of improvement, and the article I wrote below is probably the next run.

The Browser is Dead; Long Live the Browser

The traditional web browser is becoming obsolete. As we shift from navigating information to achieving outcomes, a new paradigm is emerging—one driven by intelligent agents that get jobs done. Here’s what the future holds and how to prepare for it.The Practical Innovator's Guide to Customer-Centric Growth is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Fifth Principle: A New Business Model—From Engagement to Outcome-as-a-Service

A paradigm shift in technology necessitates a paradigm shift in the business model. The current app economy is built almost entirely on one currency: your attention.

The dominant business models—advertising and subscriptions—are optimized for engagement. They succeed when you spend more time scrolling, clicking, and tapping inside their silo. This creates a fundamental conflict of interest between the developer and you. You want to get your job done and move on. They, financially, need you to stick around. This is why our devices are so noisy and distracting; they are designed to be.

An outcome-driven OS, whose entire purpose is to help you achieve your goals with minimal interaction, is fundamentally incompatible with the engagement economy. Its success metric is the opposite: to reduce the time you spend managing the machine.

Therefore, we need a new business model.

The Rise of Outcome-as-a-Service (OaaS)

The most logical model is Outcome-as-a-Service (OaaS). In this model, you don’t pay for the tools; you pay for the results.

Subscription for Outcomes: You might pay a monthly subscription to the OS provider for the ability to successfully complete a certain number or class of outcomes. A “personal” tier might handle all your scheduling, travel, and communication, while a “professional” tier adds complex project management and research capabilities.

Value-Sharing: For outcomes that generate clear economic value, the OS could take a small percentage of the value created. If the OS saves you $200 on a flight by using a negotiating agent, it might take a 5% commission on the savings. This perfectly aligns the incentives of the provider and the user. Both parties win when the user gets a better outcome.

This shift would have profound implications. It would upend the entire app store economy. Developers would no longer compete to be the most engaging app; they would compete to be the most effective service in the execution layer. Their customers would be the OS platforms and their agentic systems, which would select services based purely on their efficiency, cost, and reliability in getting a specific part of a job done.

This creates a true meritocracy of function. The best service wins, not the one with the biggest marketing budget or the most addictive design. The result is a healthier, more productive digital ecosystem where the entire system is finally, and truly, aligned with your success.

The Future Is Being Built Today

The transition from a tool-centric to an outcome-centric world won’t happen overnight. But the five principles we’ve discussed—deconstructing the app model, focusing on Jobs-to-be-Done, raising the level of abstraction, building an agentic engine, and aligning the business model with user outcomes—provide a clear and powerful blueprint.

This is more than just a new user interface. It’s a fundamental reimagining of the relationship between humans and computers. It’s about moving from a world where we serve our tools to a world where our tools serve our progress.

For the developers, designers, and strategists reading this, the call to action is to start thinking beyond the confines of the app container. Start asking not “what can our app do?” but “what job is the user trying to get done, and how can we contribute to that outcome?” The companies that embrace this shift will build the platforms of the future. Those that remain tethered to the app-centric, engagement-first model will become relics of a bygone era. The future of the OS is not in your hands; it’s in getting things done for you.

Frameworks for Innovation in an Outcome Economy

To begin building in this new paradigm, you need practical tools for brainstorming and strategy. Below are two powerful frameworks that can help you think systematically about creating value in an outcome-driven world.

A Perspective on the 10 Types of Innovation

Doblin’s framework is brilliant because it forces you to think beyond just making a better product. It shows that meaningful innovation can happen across ten different dimensions, grouped into three categories. In the context of an Agentic OS, this is particularly useful.

Configuration (The “How We Make Money & Organize”):

Profit Model: This is the core of our fifth principle. Instead of selling apps (a product), you’re selling results (a service). This is a profit model innovation.

Network: How could you create a network of users whose agents learn from each other to become more effective?

Structure: How would you need to organize your company to excel at orchestrating services rather than building monolithic apps?

Process: What is your signature process for translating user intent into a successful outcome better than anyone else?

Offering (The “What We Offer”):

Product Performance: This is the least important area. A single “killer feature” is less relevant than the overall system’s ability to deliver the outcome.

Product System: This is the most important area. The innovation isn’t in any single agent but in how the entire system of agents works together to achieve a goal.

Experience (The “How We Interact”):

Service: How do you provide support when an outcome isn’t achieved correctly? The service model shifts from “app support” to “goal support.”

Channel: The channel is no longer an app store. It’s the ambient, conversational layer of the OS itself.

Brand: Your brand is no longer about a cool icon; it’s about being the most trusted and effective partner in achieving goals.

Customer Engagement: Engagement is redefined. It’s not about keeping users hooked; it’s about building trust and demonstrating value so they delegate more important jobs to your system.

Using this framework, you can see how the Agentic OS isn’t just a product innovation; it’s a full-stack business model, process, and experience innovation.

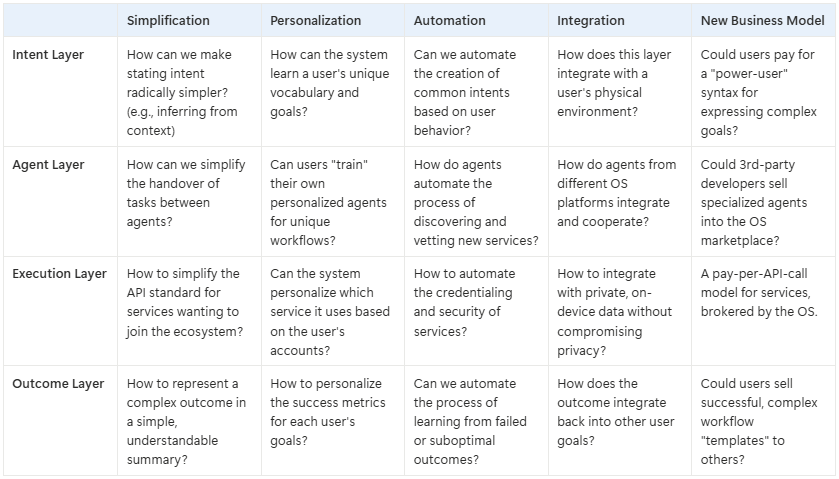

Creativity Matrices Reference Table

This table is a simple but powerful tool for structured brainstorming. You list key components of your system on one axis and innovation drivers on the other. The intersecting cells become prompts for new ideas. This helps break you out of conventional thinking.

I make content like this for a reason. It’s not just to predict the future; it’s to show you how to think about it from first principles. The concepts in this blueprint are hypotheses—powerful starting points. But in the real world, I work with my clients to de-risk this process, turning big ideas into capital-efficient investment decisions, every single time.

Follow me on 𝕏: https://x.com/mikeboysen

If you’re interested in inventing the future as opposed to fiddling around the edges, feel free to contact me. My availability is limited.

Mike Boysen - www.pjtbd.com

De-Risk Your Next Big Idea

Masterclass: Heavily Discounted $67

My Blog: https://jtbd.one

Book an appointment: https://pjtbd.com/book-mike

Join our community: https://pjtbd.com/join