This is a long one for my paid subscribers. I didn’t want to break it into a series so you won’t be able to read it all in your email client. Sorry.

Downloadable cheat sheet at the end.

Part 1: The Trap of the “Solution”

Chapter 1: The Most Expensive Words in Business: “What’s the Solution?”

The demand arrived, as it so often does, with the force of a royal decree. It came from the new, high-energy VP of Sales at a mid-stage SaaS company—let’s call him Mark. Mark was a celebrated hire, brought in to “pour gas on the fire” and scale revenue. After three weeks on the job, he called an “urgent, all-hands” meeting with the product and engineering leads.

“Our sales data is a black box,” Mark declared, pacing in front of a whiteboard. “My reps are flying blind. They’re wasting half their day digging through reports to figure out who to call. We have no visibility, no predictability.” He uncapped a red marker. “We need a new dashboard. I’m calling it ‘Project Apex.’ It needs to show real-time rep activity, lead conversion rates by source, and pipeline velocity, all on one screen. This is our number one priority. What’s the solution?”

The product manager, pressured by the force of Mark’s certainty, nodded. The engineering lead, already calculating the backend lift, began to talk about data warehousing. The “pain point” had been identified—”We have no visibility”—and a “solution” had been named: “Project Apex.”

The team was assembled. A tiger team was formed. Sprints were planned. For six months, “Project Apex” consumed the company’s best engineers. Other, murkier product initiatives—like a thorny, hard-to-define “user activation” project—were back-burnered. Finally, after a $500,000 burn in salaries and resources, “Project Apex” was launched with a virtual party and company-wide fanfare.

Six weeks later, the dashboard’s daily active user count was three.

Mark, the VP, was one. The product manager was the second. The third was a new sales rep who left it open on a second monitor because he thought it “looked productive.” The sales team’s behavior hadn’t changed at all. The needle on “pipeline velocity” hadn’t budged.

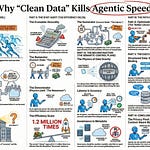

The problem, as a painful post-mortem later revealed, was never “visibility.” The real problem was that the company’s sales compensation plan was structured to reward any closed deal, regardless of its size or long-term value. The sales team knew who to call: the easy, low-value clients who would sign quickly, securing their monthly bonus. They didn’t want a dashboard that highlighted the harder, more complex, high-value leads. “Project Apex” was a brilliant, half-million-dollar solution to a problem that never existed.

This story is not an anomaly. It is the default state of modern business. We are organizations addicted to “solutions,” and this addiction is the single greatest barrier to meaningful innovation. The most expensive words in business are not “We failed.” They are, “What’s the solution?”

This phrase is a trap. It is a siren call that lures teams into the deadly, shallow waters of building the wrong thing. It’s the “pain point paradox”: the moment a problem is loudly and clearly articulated as a “pain point,” it is almost certainly a symptom, not the root cause. And by demanding an immediate “solution,” we are, by definition, asking our most creative people to architect a fix for a symptom.

The Anatomy of a “Pain Point”

Before we can dismantle this reflex, we must understand what a “pain point” truly is. It is not, as commonly believed, the problem itself. A “pain point” is the symptom—the tangible friction, the emotional frustration, the surface-level irritation. It is the fever, not the infection.

A classic “pain point” is typically a three-part construct:

A Surface Observation: “This report takes five minutes to load.”

An Emotional Reaction: “It’s frustrating and makes me feel like my time is being wasted.”

An Implied, Unvalidated Solution: “We need to make the report faster.”

The “solution-jumper” hears this and immediately opens a ticket to optimize the database query. The true practitioner—the problem-architect—hears this and asks, “Why are we running this report in the first place?”

Why Our Brains Are Hardwired for “Solution-Jumping”

This “solution-jumping” is not a personal failing; it is a deep-seated cognitive and cultural reflex. Our brains are hardwired for it. We are biased toward action. Faced with ambiguity and a clear expression of discomfort (the “pain point”), our minds—evolved to be “satisficing” machines, not “optimizing” ones—will seize the first “good enough” answer. It feels better to do something (optimize the query) than to do nothing (pause and ask more questions).

This cognitive bias is then amplified by corporate culture. We lionize the firefighter, the “doer,” the “closer.” We celebrate the person who “gets things done.” The product manager who can take a “pain point” from a VP and “deliver a solution” in six months is seen as effective.

The person who responds to the VP’s demand with a series of probing, difficult questions, on the other hand, is often perceived as a “bottleneck,” “overly-academic,” or “not a team player.” Our very incentive structures are designed to reward the swift delivery of solutions, not the patient, disciplined deconstruction of problems.

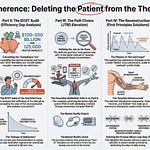

The Strategic Cost of Fixing Symptoms

The cost of this reflex is not measured in a single failed project. The half-million dollars spent on “Project Apex” was not the real loss. The true costs are far deeper, and they are threefold:

Massive Opportunity Cost: The primary cost was not the money spent; it was the time. Those six months of your best engineers’ lives are gone forever. The true, multi-million-dollar “user activation” project that could have bent the curve of the entire company was left to stagnate.

Strategic Debt: When you build a “solution” to a symptom, you don’t just waste time. You create “strategic debt.” “Project Apex” now has to be maintained. It has to be updated with every API change. It has become a permanent, calcified part of your codebase and your strategy, forever obscuring the real problem—the misaligned sales incentives. Fixing the symptom has, in effect, made it harder to identify and fix the disease.

Cultural Erosion: Finally, and most insidiously, you create a culture of cynicism. The engineers on the “Project Apex” team know no one uses their product. They will be less motivated, less creative, and less trusting on the next project. You have signaled to your entire organization that high-stakes, high-effort work can be, and often is, completely pointless.

To break this cycle, we do not need faster developers or more elaborate roadmaps. We need a new tool. We need a way to resist the “solution-jumping” reflex and buy ourselves the time to find the real problem. We need a method that is disciplined, rigorous, and—when wielded correctly—collaborative.

We need a scalpel to dissect the “pain point,” cut through the layers of assumptions, and reveal the fundamental “first principles” of the problem beneath. That tool, sharpened over 2,400 years, is the Socratic method.

Chapter 2: The Socratic Scalpel: A Tool for Deconstruction, Not Interrogation

The “Socratic method.” The phrase itself is part of the problem.

For most people, it conjures one of two images: a dusty philosophy lecture, or the discomfort of a hostile cross-examination. It feels academic at best and combative at worst. To a time-pressured executive like Mark, in the “Project Apex” example, responding to his urgent demand with “I’d like to engage in some Socratic questioning” is a surefire way to be labeled an obstacle.

This is the central barrier to its use: a fundamental misunderstanding of the tool itself.

We must, therefore, reclaim the Socratic method for what it truly is: not a club for winning arguments, but a scalpel for collaborative discovery. A surgeon uses a scalpel not to attack a patient, but to work with them—to precisely cut away the superficial layers, bypass the non-essential tissue, and reveal the true source of the problem. It is a tool of healing, of precision, and, above all, of partnership. When we adopt this “Socratic scalpel” mindset, the entire dynamic shifts.

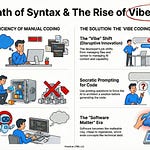

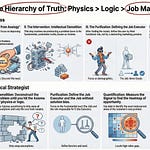

From “Why?” to “Why Do We Believe This?”

The second barrier is a confusion of tools. Most people mistake the Socratic method for the “Five Whys,” the technique popularized by Toyota. The “Five Whys” is a powerful tool for finding the causal root of a problem. (e.g., “The machine stopped.” “Why?” “The fuse blew.” “Why?”...). It is linear and diagnostic.

The Socratic scalpel operates on a different axis entirely. It is not concerned with the causal chain, but with the belief chain. It seeks the epistemological root—not “why did this happen?” but “why do we believe this to be true?”

This is a profound shift.

The Five Whys asks: “Why did the sales reps stop using the old reports?”

The Socratic Scalpel asks: “Why do we believe the problem is ‘visibility’ in the first place?”

This second question is infinitely more powerful. It stops you from optimizing a report (a “solution”) and forces you to question the very foundation of the demand. It is the one tool that gives you permission to dissect the brief itself.

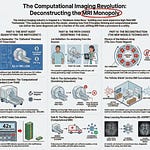

Setting the Stage: Psychological Safety and the “Shared Goal” Frame

You cannot, however, simply walk up to a stakeholder and ask, “Why do you believe that?” The Socratic scalpel is useless without an operating room. That operating room is a state of psychological safety, which you, the practitioner, must build in seconds.

You do this by explicitly framing the exercise around a shared goal and a shared risk. It is never “me vs. you”; it is “us vs. the problem.”

Here is the frame:

“Mark, I am 100% aligned with you on the goal of increasing pipeline velocity. That is the mission. Because that mission is so critical, I want to de-risk this ‘Project Apex’ before we commit millions of dollars and six months of our best engineers’ time. What I’d like to do is partner with you for one hour to use this framework to pressure-test our core assumptions. My only goal is to make absolutely certain that what we build will solve the problem, and that we build it right, once.”

In this frame, your questioning is no longer an interrogation; it is an act of fiscal and strategic responsibility. You have transformed yourself from a “bottleneck” to a “co-architect.”

You have now earned the right to begin. You have established the psychological safety to move from the chaotic, high-pressure demand for a solution to the calm, disciplined deconstruction of the problem. You are ready for Phase 1.