Y-Combinator's NOSO LABS is building an AI sales tool for field techs. Here's a detailed blueprint for how they could become the central nervous system for all industrial operations by applying First Principles, JTBD, and the 10 Types of Innovation.

The Allure of the Obvious Problem

If you follow the Y-Combinator batches, you’ll see a pattern. You’ll find dozens of companies building clean, AI-powered SaaS tools to solve a visible, tangible problem for a specific user. It’s a proven playbook: find a workflow, find the friction in that workflow, and apply software to reduce the friction.

NOSO LABS is a perfect product of this playbook. Their pitch is simple and easy to grasp: they provide AI agents to help field service technicians diagnose and sell more effectively. You can immediately picture it. A technician is on-site, a complex piece of HVAC equipment is down, and instead of flipping through a manual, they talk to an AI that guides them through diagnostics and helps them quote the right repair package to the customer.

It’s a good idea. It’s a tangible improvement. It will likely find customers.

And it’s also a massive strategic trap.

This company, like so many others, is diligently applying a 10% solution to a surface-level problem. It’s a local optimization. They’re helping the technician perform a job that their customer fundamentally wishes they didn’t have to do in the first place. No one wants to buy a repair. A repair is the expensive, disruptive, and stressful result of a failure.

The real, billion-dollar opportunity isn’t in making the moment of failure slightly more efficient. It’s in creating a world where that failure never happens at all.

This post is a detailed, forensic teardown of NOSO LABS’s current strategy and a blueprint for a strategic pivot. We are going to use a sequence of foundational business frameworks to break their model down to its core truths and rebuild it from the ground up. You’ll see how a simple shift in perspective—from the technician’s immediate task to the customer’s ultimate goal—transforms a simple SaaS tool into an industry-defining platform.

We will:

Deconstruct the current business model using First Principles Thinking to expose the fragile assumptions it’s built on.

Reconstruct a new, vastly more valuable business by identifying the true Job-to-be-Done of the economic buyer.

Evaluate how this new business can build a nearly uncopyable competitive moat using Doblin's 10 Types of Innovation.

This isn’t just a critique of one company. It’s a guide for any founder, investor, or product leader who senses they might be solving an obvious problem instead of an essential one. Let’s dive in.

Deconstructing the Premise

First Principles Thinking is a deconstruction methodology. You break a complex problem down not into smaller problems, but into its most basic, foundational truths—the things you know to be true without assumption. Elon Musk used it to conclude that rockets could be 100 times cheaper; we’re going to use it to analyze a business model.

Let's start by stating the current assumptions underpinning NOSO LABS and break them down.

Assumption 1: The technician’s job is to diagnose and sell.

This is the most dangerous kind of assumption because it’s partially true. Yes, a technician’s daily tasks involve diagnosis and quoting repairs. But reasoning from analogy—"we’re like a better manual and sales script"—is a strategic dead end. Let’s apply First Principles.

What is a field technician? A person sent to a location to resolve an issue with a piece of equipment.

Why are they there? Because the equipment is broken or not performing as expected.

Why is that a problem? Because the customer—the business or homeowner—relies on that equipment to achieve a goal. A broken HVAC system means a home is uncomfortable or a business may have to close. A broken manufacturing robot means a production line stops, costing thousands of dollars per minute.

What, then, is the fundamental goal of the customer? It is not to interact with a technician. It is not to buy a repair. The goal is the outcome the equipment provides. For a factory owner, the goal is operational uptime. For a homeowner, it’s a comfortable and safe environment.

What is a "repair" from first principles? It is a corrective action applied after a failure has already occurred. It is a sign that the system has failed. It is inherently reactive.

Fundamental Truth: The customer hires the equipment to do a job. They hire the technician only when the equipment fails to do that job. Therefore, the technician's visit represents a failure in the customer's world. Optimizing the efficiency of this failure state is a valuable, but limited, endeavor. NOSO LABS, in its current form, is a painkiller for the symptom (inefficient repairs) rather than a cure for the disease (unexpected downtime).

Assumption 2: The technician is the right user to empower.

The technician is the most visible person in the process, making them an obvious user to target. But are they the person with the most at stake? Are they the true economic buyer?

Who feels the pain of a broken machine most acutely? Not the technician—for them, it’s another job ticket. The real pain is felt by the business owner whose revenue stops, the operations manager whose performance metrics plummet, or the CFO who has to approve a massive, unbudgeted capital expenditure.

Who makes the strategic decisions? The technician might choose a wrench, but the operations manager chooses the maintenance strategy. They decide on reactive vs. preventative vs. predictive maintenance. They own the budget and are responsible for the business outcomes.

What is the "job" of the operations manager? To manage risk, control costs, and maximize the output of their systems. An unexpected failure is a direct threat to all three of these objectives.

How would this person measure success? Not by how quickly a technician can sell them a repair. They measure success in metrics like Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE), Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF), and, most importantly, the reduction of unplanned downtime.

Fundamental Truth: The technician is a crucial actor in the system, but the economic buyer and the person responsible for the strategic goal is the operations manager or business owner. A solution that empowers the technician is a tool. A solution that empowers the manager to eliminate the problem is a strategic platform. By focusing on the technician, NOSO LABS has anchored its value to the tactical level, leaving the strategic, high-value opportunity on the table.

Assumption 3: A conversational AI is the best solution.

The current hype cycle makes it easy to assume that applying a Large Language Model (LLM) is the most innovative path. But is it the most fundamental way to solve the problem of equipment failure?

What causes equipment to fail? From first principles, it’s physics. Material fatigue from vibration. Overheating that degrades components. Electrical resistance changes. Contamination of lubricants. These are measurable, physical phenomena.

When do these causes become knowable? Not at the moment of failure. They are detectable before failure. A bearing develops a microscopic vibration pattern weeks before it seizes. A motor’s temperature profile begins to creep up long before it burns out.

What is the most fundamental way to prevent failure? To monitor the underlying physical state of the equipment and identify these leading indicators.

What is the role of AI here? A conversational AI for diagnosis is, by definition, used after the failure has occurred. A more powerful application of AI would be in pattern recognition and predictive modeling based on sensor data—to predict and prevent the failure in the first place.

Fundamental Truth: The most effective solution to preventing downtime is rooted in data and physics, not conversation. A reactive diagnostic chatbot is a clever user interface for a low-value moment in time. A proactive, data-driven predictive engine is a fundamental solution to the customer's core problem.

By deconstructing these three core assumptions, the facade of the "AI sales tool" falls away. We're left with a set of foundational truths that point toward a much larger, more valuable opportunity. Let's use them to build it back up.

Reconstructing the Opportunity

Now that we’ve broken the problem down, we can rebuild a solution from the ground up. The Jobs-to-be-Done (JTBD) framework is perfect for this because it forces us to focus on the customer’s ultimate goal, not their tasks. The core principle of JTBD is that people don't buy products; they "hire" them to get a job done. Our goal is to define the real job the customer is trying to do.

As we discovered in our First Principles analysis, the current model focuses on the wrong job and the wrong person. Let’s correct that.

The Wrong Job: Help a technician diagnose and sell a repair.

The Right Job: Enable an operations manager to ensure continuous operational uptime of their business-critical systems.

This single sentence changes everything. It elevates the company from a tool-maker to a strategic partner. It changes the customer from a cost-conscious field service manager to a value-focused operations executive. It changes the product from a chatbot to a central nervous system.

Let's build out the full picture of this new opportunity.

Defining the New Market

Old Market: Field Service Management Software (a crowded, feature-based red ocean).

New Market: Operational Uptime Assurance (a new category of value-based blue ocean). This market is not defined by a type of software, but by a group of people (operations managers) trying to get a job done (ensure uptime). Their competition isn't another diagnostic tool; it's hiring more technicians, buying redundant equipment, or simply absorbing the high cost of downtime.

The Job Performer

Primary Performer: The Operations Manager, Head of Maintenance, or Plant Manager. This is the person whose career success is tied to the performance of the assets.

The Core Functional Job: Ensuring continuous operational uptime of business-critical systems.

To understand this job, we can map it out using the universal Job Map structure. This isn't about the customer's journey with our product; it's a solution-agnostic map of what they are already trying to do, even if they’re using a messy combination of spreadsheets, gut instinct, and prayer.

A Detailed Job Map for 'Ensuring Uptime'

Define:

What they’re trying to do: Determine which pieces of equipment are most critical to the business and establish the acceptable parameters for their performance.

Pain Points: This is often based on tribal knowledge rather than data. The financial impact of a specific machine's failure is often unknown until it's too late.

Locate:

What they’re trying to do: Gather all relevant data streams needed to understand the health of the assets. This includes maintenance logs, usage data from the machine's PLC, and readings from any existing sensors.

Pain Points: Data is siloed in different systems (CMMS, SCADA, ERPs) and is often incomplete or in inconsistent formats.

Prepare:

What they’re trying to do: Organize and integrate the located data into a single, usable view. Set up monitoring dashboards and alert thresholds.

Pain Points: This requires significant manual effort, custom development, or expensive, hard-to-configure software. It's a massive headache.

Confirm:

What they’re trying to do: Verify that the monitoring system is working correctly and that the alert thresholds are meaningful before relying on it for critical decisions.

Pain Points: It's hard to know if an alert is a false positive or a real signal. Trust is low.

Execute:

What they’re trying to do: Take proactive actions based on the data to prevent failures. This includes scheduling maintenance at the optimal time (not too early, not too late) or adjusting how the equipment is used.

Pain Points: Often defaults to a simple time-based schedule ("service every 6 months") which is inefficient and doesn't prevent all failures.

Monitor:

What they’re trying to do: Continuously track the real-time health and performance of the critical assets against the defined parameters.

Pain Points: "Monitoring" often means waiting for a red light to turn on, which means the failure has already begun.

Modify:

What they’re trying to do: Make real-time adjustments to the system to prevent a predicted failure. This could mean reducing the speed of a machine, re-routing production, or ordering a part before it's needed.

Pain Points: This level of proactive control is a pipe dream for most organizations. They are stuck in a reactive fire-fighting mode.

Conclude:

What they’re trying to do: Quantify the success of their uptime strategy. Report on the financial impact of prevented downtime and justify the investment in their programs.

Pain Points: It’s very difficult to prove the value of a failure that didn’t happen, making it hard to secure budget and headcount.

This Job Map is a goldmine. Each step is filled with significant, unmet needs. The NOSO LABS diagnostic tool serves a tiny fraction of one step (Execute) in a much larger, more valuable process. The reconstructed company would build a platform to get the entire job done … on a single platform. 😉

Emotional & Social Jobs

Beyond the functional job, the operations manager is also trying to make progress in their professional life. A platform that only addresses the functional steps will miss the powerful emotional drivers.

Emotional Jobs:

Reduce the stress of late-night calls about a critical failure.

Feel in control of the operational environment, rather than at the mercy of it.

Gain confidence in the decisions being made about maintenance and capital expenditures.

Social Jobs:

Be seen as a strategic contributor to the company's bottom line, not just a manager of a cost center.

Be perceived as an innovator who is bringing modern data practices to a traditional field.

A platform that helps an operations manager sleep better at night and get promoted is a platform that will never be churned.

Designing Novel Concepts for the Reconstructed Business

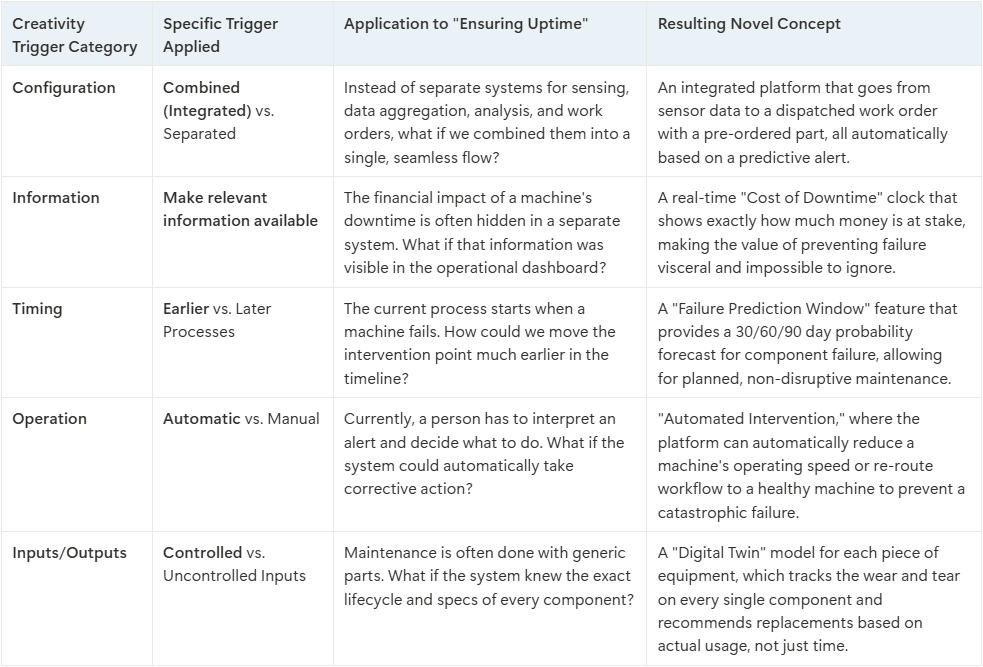

By understanding this deep and complex job, we can brainstorm novel solutions that are far more powerful than a simple chatbot. We can use creativity triggers to systematically challenge the status quo.

These concepts get the entire job done in a completely different way—better, at a lower total cost, and with fewer visible features for the end-user to manage. The diagnostic chatbot becomes an obsolete feature in a world where the system tells you what to fix long before it breaks.

Building an Uncopyable Moat

A great idea is not enough. A truly defensible business builds a competitive moat that makes it difficult, expensive, and time-consuming for others to copy. The problem with NOSO LABS's current model is that its moat is shallow. It's a Product Performance innovation (a better AI) which is the easiest type for competitors to replicate.

The reconstructed business, however, can build a deep, compounding moat by weaving together multiple types of innovation. This is how you move from a product, to a platform, to an ecosystem.

Profit Model Innovation: From SaaS to Uptime-as-a-Service

This is the most powerful strategic lever. Instead of selling a software subscription for $50/technician/month, you change the entire value equation.

The New Model: Customers don't pay for software. They pay a monthly fee for a guaranteed level of operational uptime. For example, the company might charge $10,000/month for a critical production line and in return, guarantee 99.9% uptime. If they fail to meet that Service Level Agreement (SLA), they pay a penalty.

Why it's a Moat:

Value Alignment: Your incentives are perfectly aligned with your customer's. You only make money if they succeed. This transforms your relationship from a vendor to a partner.

Barriers to Entry: This is incredibly difficult for a traditional SaaS company to copy. It requires a deep understanding of actuarial risk, industrial processes, and the ability to underwrite performance guarantees. It's a data science and financial engineering problem, not just a software problem.

Predictable Revenue: While it seems risky, as your predictive models improve, your costs to deliver the service decrease, making your margins expand over time.

Process Innovation: Proprietary Predictive Analytics

The AI is no longer a user-facing chatbot; it's the core intellectual property of the company, running in the background.

The New Process: The platform ingests vast amounts of sensor data from across a customer's fleet of equipment. The proprietary AI models, which are constantly learning, analyze these patterns to predict failures with increasing accuracy. This predictive process is the engine that enables the entire business model.

Why it's a Moat:

Data Network Effects: The more data the system processes, the smarter it gets. Your models, trained on data from hundreds of customers, will become far more accurate than any single-tenant system a competitor could build. Every new customer makes the service better for every existing customer.

Tacit Knowledge: This process becomes a "black box" of expertise that is impossible to reverse-engineer. It is the company's signature method for turning raw data into financial value.

Network Innovation: The OEM & Insurance Ecosystem

You can't do this alone. The smart move is to build a network that locks out competitors.

The New Network:

OEM Partnerships: Partner with the manufacturers of the equipment (the Rockwell Automations, an Siemens of the world). They can pre-install your sensors and software on their machines at the factory. For them, it’s a way to sell a more reliable product. For you, it’s an unbeatable distribution channel.

Insurance Partnerships: Partner with industrial insurance companies. They lose billions when a factory has a catastrophic failure. Your platform is a risk-reduction tool. They can offer lower premiums to customers who use your system, creating a powerful financial incentive to adopt your platform.

Why it's a Moat: These exclusive partnerships create a self-reinforcing ecosystem. If every new piece of equipment comes with your platform integrated, and every insurance policy rewards you for using it, it becomes the industry standard by default.

Product System & Service Innovation: From Software to a Turnkey Solution

Finally, you wrap the entire offering in a system and service layer that is impossible for a simple software company to match.

The New System: The offering isn't just a dashboard. It's an integrated system of proprietary sensors, edge computing hardware, a cloud analytics platform, and workflow automation tools. You might even supply the replacement parts, ordered automatically by the system.

The New Service: You don't just offer "customer support." You offer "Customer Success." This means dedicated reliability engineers who work with your clients to analyze the data, fine-tune the models, and implement the operational changes needed to maximize uptime. They become trusted advisors, deeply embedded in the customer's workflow.

Why it's a Moat: This creates incredibly high switching costs. To leave your platform, a customer would have to rip out hardware, retrain their team, lose all their historical data and predictive models, and abandon their relationship with their dedicated success engineer. It's simply not worth it.

When you combine these innovations—a revolutionary Profit Model, a proprietary Process, a locked-in Network, and a high-friction Product System/Service—you create a fortress. A competitor can’t just copy your chatbot's UI. They have to replicate your entire business architecture. This is how you build a company for a decade, not just for an exit.

The Accelerator Blind Spot: Why Foundational Strategy Gets Overlooked

If this pivot is so obvious, why isn't it the default path? Why do smart founders and experienced investors at places like Y-Combinator so often fund the surface-level solution?

The answer lies in the incentive structure of the accelerator model itself. The system is optimized for a specific type of company: a highly scalable, low-friction, B2B SaaS business with predictable metrics.

The Pressure for Traction: Founders have 3 months to show meaningful progress for Demo Day. It is infinitely faster to build a simple AI wrapper and show engagement metrics from a few pilot users than it is to conduct deep market research, build partnerships with industrial giants, and develop a complex risk model for uptime guarantees.

The Worship of SaaS Metrics: The language of early-stage investing revolves around MRR, CAC, LTV, and churn. The "Uptime-as-a-Service" model doesn't fit neatly into this spreadsheet. Its sales cycles are longer, its initial implementation is more complex, and its value is harder to quantify in the first 90 days. It requires a different kind of investor with a different kind of patience.

The "Software Will Eat the World" Bias: There's a prevailing belief that the best solution is always a pure software solution because it has zero marginal costs. The reconstructed business model we've outlined involves hardware (sensors) and people (success engineers). This is often seen as "unscalable" or "messy" in a world that fetishizes pure software plays.

This systemic pressure creates a blind spot. It encourages founders to find a nail that looks like it can be hit with a software hammer, rather than stepping back and asking if they should be building something else entirely. They are incentivized to pursue the local optimum—the quick win, the easy-to-measure progress—at the expense of the global optimum, which is the truly transformative, market-defining opportunity.

The irony is that the foundational work we’ve just walked through—the First Principles deconstruction and JTBD reconstruction—is the ultimate way to de-risk a business. It provides a level of strategic clarity and conviction that can't be gained from shipping features and A/B testing landing pages. Accelerators would provide far more value if they spent the first month forcing founders through this rigorous process before a single line of code is written.

From Feature to Bedrock

NOSO LABS stands at a crossroads, and their position is symbolic of a challenge facing hundreds of startups today.

Path A is the path of least resistance. They can continue building a better AI sales and diagnosis tool for technicians. They can become a useful feature, a nice-to-have in the crowded Field Service Management market. They might get acquired by a larger player for a modest sum to be integrated into a bigger suite. It is a viable path.

Path B is the path of profound ambition. They can choose to solve the problem behind the problem. They can pivot from helping people react to failure to building the platform that makes failure obsolete. They can change their customer, their business model, and their definition of success. They can become the foundational bedrock of industrial operations—the trusted partner that guarantees the output of the physical world.

This pivot requires more than just a different product roadmap. It requires a different kind of courage. It requires a willingness to abandon the easy-to-explain idea for the hard-to-build system. It requires a commitment to building a company with a deep, uncopyable moat based on a fundamental understanding of customer value.

For founders, the lesson is clear: don't fall in love with your solution. Fall in love with your customer's job. Deconstruct every assumption about the problem you think you're solving. Reconstruct your business around the progress your customer is truly trying to make.

For investors, the challenge is to look beyond the tidy SaaS metrics and learn to identify the teams that have done this foundational work. These are the companies that will not just capture a piece of an existing market, but will create entirely new ones.

The billion-dollar opportunity for NOSO LABS isn't in their code; it's in their courage to see the iceberg beneath the tip. It's hiding in plain sight.

Follow me on 𝕏: https://x.com/mikeboysen

If you'd like to see how I apply a higher level of abstraction to the front-end of innovation, please reach out. My availability is limited.

Mike Boysen - www.pjtbd.com

Why fail fast when you can succeed the first time?

Masterclass: https://pjtbd.com/mc

My Blog: https://jtbd.one

📆 Book an appointment: https://pjtbd.com/book-mike

Join our community: https://pjtbd.com/join