The Illusion of Optimization

Take a moment and think about the last piece of fruit you ate. An apple, maybe a banana. Now, try to imagine its journey. The odds are it was harvested thousands of miles away, passed through the hands of a packer, a freight forwarder, a wholesaler, and a distributor, sat in various warehouses, and traveled on multiple trucks before it finally landed in your grocery store. It’s a modern miracle of logistics.

It’s also a house of cards.

Our global food supply chain is a marvel of intricate, sprawling complexity. It’s also incredibly fragile, inefficient, and wasteful. We build these long, brittle chains and then act surprised when a single broken link—a pandemic, a blocked canal, a labor shortage—causes widespread disruption. The system creates immense waste, burns obscene amounts of energy, and leaves value on the table at every single hand-off.

I wrote an article a few months back that looks at this from a different angle

Into this chaos steps a company like Burnt. Backed by the prestigious Y Combinator, Burnt is building what it calls an "agentic operating system for the food supply chain." It's a smart, sophisticated software layer designed to bring order to the chaos, automating the orchestration of food logistics. It's the archetypal accelerator-backed solution: take a massive, messy, legacy industry and apply a dose of brilliant software engineering.

And on the surface, it makes perfect sense. The problem is obvious. The solution is elegant.

But it’s wrong.

Burnt isn't solving the problem. It's treating a symptom. It’s building a better navigation system for a fundamentally broken road network.

Venture-scale, world-changing returns don't come from optimizing broken systems; they come from making them obsolete.

True, defensible innovation requires you to ignore the system as it exists today and ask what it should be.

This post is a forensic analysis of that idea. We’re going to apply a rigorous strategic framework that top accelerators often overlook in their rush to build and scale.

Deconstruct: We’ll use First Principles Thinking to break the entire food distribution problem down to its core, unchangeable truths—the physics and economics of moving food.

Reconstruct: We’ll use the Jobs-to-be-Done framework to define the real, high-level job that customers are trying to accomplish, ignoring the tasks and tools of the current system.

Evaluate: We’ll use Doblin's 10 Types of Innovation to design a new, superior business model with a deep, systemic competitive moat—the kind of defensibility that doesn’t just come from a better algorithm.

This is the blueprint for a more foundational, more ambitious, and ultimately more valuable alternative to what Burnt is building. It's the kind of strategic thinking that accelerators should be demanding from their founders.

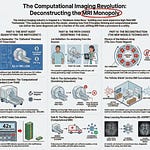

Part 1: Deconstruction - The First Principles of Food Distribution

To see why Burnt’s approach is a temporary patch, not a permanent solution, you have to stop looking at the supply chain itself. You have to ignore the warehouses, the shipping manifests, and the trucking routes. You have to go deeper, down to the fundamental forces that govern the entire system.

The prevailing assumption baked into Burnt’s model—and the entire industry—is that this complex, multi-layered, coast-to-coast food supply chain is an immutable reality. Their software is designed to help companies operate within that reality more efficiently.

But what if that reality is just a set of workarounds for a few simple, fundamental truths? When you apply First Principles Thinking, you can boil the entire industry down to four core axioms.

Axiom 1: Perishability (A Law of Biology)

This is the most fundamental truth. Food is organic matter. From the moment it's harvested, a clock starts ticking. Biology dictates that it will decay. The entire cold chain—refrigerated trucks, warehouses, and grocery aisles—is a brute-force attempt to slow down this universal constant. Every hour food spends in transit or storage is an hour it loses freshness, nutritional value, and, eventually, edibility.

The Goal of Innovation: The only way to truly "solve" for perishability is to radically minimize the time variable.

Axiom 2: Distance (A Law of Physics)

This is the second truth. To move a physical object (like an apple) from Point A to Point B requires energy. Moving billions of apples billions of miles requires a staggering amount of energy, which has a direct and unavoidable cost (fuel, labor, infrastructure maintenance). Our current system is built on the belief that it’s cheaper to grow food in massive, centralized locations and ship it everywhere than it is to grow it closer to where it’s consumed. For a long time, thanks to cheap fossil fuels, that was true. But it’s a dependency, not a law of nature.

The Goal of Innovation: The only way to truly "solve" for the cost of distance is to radically minimize the distance variable itself.

Axiom 3: Information Asymmetry (An Economic Artifact)

This is where things get interesting. In a pre-digital world, the person who grew the apple had no efficient way of knowing who wanted to buy it in a city 2,000 miles away. Likewise, the city grocer had no way of knowing the quality and availability of apples from a thousand different farms. This information gap created an opportunity for intermediaries: wholesalers, distributors, brokers. They created value by aggregating information. They bought in bulk, managed risk, and became the source of truth for both sides. For this service, they extracted a significant margin.

This is the axiom that Burnt is attacking. Their "agentic OS" is a powerful information tool. It creates transparency, reduces uncertainty, and automates communication. It attacks the information asymmetry that allowed intermediaries to flourish.

The Goal of Innovation: Eliminate the information gap so that producers and consumers can connect more directly, removing the need for costly intermediaries.

Axiom 4: Transactional Friction (An Economic Cost)

Every time that apple changes hands—from farmer to packer, packer to wholesaler, wholesaler to distributor, distributor to retailer—it creates friction. Each hand-off requires a contract, an invoice, insurance, quality verification, and a transfer of payment. Each of these steps adds administrative overhead, cost, and, crucially, delay. This friction is the glue that holds the intermediary-heavy model together.

The Goal of Innovation: Design a system with the fewest hand-offs possible, ideally just one: from producer to consumer.

The Inescapable Conclusion

When you look at the problem through this lens, Burnt’s limitation becomes crystal clear. Their software is a world-class solution for Axiom 3. It brilliantly reduces the cost of information asymmetry.

But it fully accepts Axioms 1, 2, and 4 as fixed, unchangeable costs of doing business.

It doesn’t shorten the time to spoilage. It doesn’t reduce the physical distance food has to travel. And while it may smooth out the transactions, it doesn't eliminate the number of hand-offs. It is, in essence, a digital lubricant for an analog machine.

True, profound disruption doesn’t come from lubricating the old machine. It comes from designing a new one that renders the old axioms irrelevant.

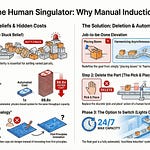

Part 2: Reconstruction - The Real Job of Getting Food to People

If deconstruction is about finding the fundamental problem, reconstruction is about defining the ideal solution. To do that, we need to use the Jobs-to-be-Done (JTBD) framework. This means we have to stop thinking about the tools and processes of the existing industry and focus on the customer's ultimate goal.

The mistake is thinking the job is "orchestrate food logistics." That's a description of a task within the current, broken system. We need to elevate the level of abstraction to find the real, underlying human need.

The higher-level job is: "sustain human populations with reliable, nutritious, and affordable food."

That’s it. That’s the real job. Everyone—from the farmer to the truck driver to the family at the dinner table—is a stakeholder in getting this one, massive job done. When you frame it this way, a logistics OS seems like a minor optimization. The real opportunities for innovation are far bigger.

Mapping the Full Job

Now, let's break that high-level job down into its core components using a universal JTBD Job Map. What are the steps someone has to take to get this job done successfully?

Define: Determine what food is needed, where it's needed, and when it's needed.

Locate: Identify and source the required raw ingredients or products.

Prepare: Get the food ready for distribution (harvesting, processing, packaging).

Confirm: Verify that the prepared food meets quality, safety, and demand requirements.

Execute: Transport the food from the point of production to the point of consumption.

Monitor: Track the food's condition and location throughout the journey.

Modify: Make adjustments in response to unexpected events (delays, spoilage).

Conclude: Successfully deliver the food to the end consumer and complete the transaction.

The current system spends most of its energy on Execute, Monitor, and Modify. Burnt's software is hyper-focused there. But the biggest unmet needs—the biggest sources of waste and cost—are hidden in the other steps. The real pain points are what JTBD calls unmet "Customer Success Statements" (CSS).

For this job, the most critical unmet CSS are:

Minimize the time between the "Prepare" step (harvesting) and the "Conclude" step (consumption).

Minimize the likelihood that food is damaged or spoiled during the "Execute" step.

Minimize the total cost incurred across all steps of the map.

The current system is terrible at all three of these. Burnt helps with the cost, but not the time or the spoilage. A truly superior solution would attack all three simultaneously by redesigning the system from the ground up.

Brainstorming Superior Solutions

So, what does a system designed to nail these success statements look like? It looks nothing like the one we have today.

Concept 1 (Working Today, Underleveraged): Vertically Integrated Urban Farming Co-ops

This isn't science fiction; it's already happening in pockets. Companies are building massive vertical farms in or near cities. They can control the environment to grow produce year-round with less water and no pesticides. A network of these farms, organized as a co-op and connected by a shared tech platform, could service local restaurants, grocers, and institutions directly. They effectively delete the long-haul "Execute" step from the job map, collapsing the supply chain from thousands of miles to just a few.

Concept 2 (Novel & Disruptive): The Automated "Agri-Hub" Network

This is where we elevate the level of abstraction to create something truly new. Imagine a network of automated, modular "agri-hubs" built at the edge of every major population center.

Think of it like a cloud data center, but for food.

These hubs are not just farms or warehouses; they are multi-functional, integrated facilities that get the entire job done.

Production: A significant portion of the facility is a high-density, AI-controlled vertical farm for leafy greens, herbs, and other suitable crops.

Processing: Robotic systems handle harvesting, quality inspection, and packaging on-demand.

Logistics: The hub serves as a hyper-local fulfillment center. It dispatches orders via a fleet of autonomous ground vehicles or drones for last-mile delivery.

Consolidation: The hub also acts as a drop-off point for other local and regional producers (of things that can't be grown in a vertical farm, like grains, proteins, or orchard fruits), allowing them to tap into the hub's sophisticated processing and delivery network.

This model doesn't just optimize the old system; it inverts it. Instead of a "push" system where food is grown centrally and pushed out to the masses, it creates a "pull" system where food is grown and prepared on-demand as close to the consumer as possible. It directly attacks all four of our First Principle axioms. It minimizes time, distance, and transactional friction while destroying information asymmetry.

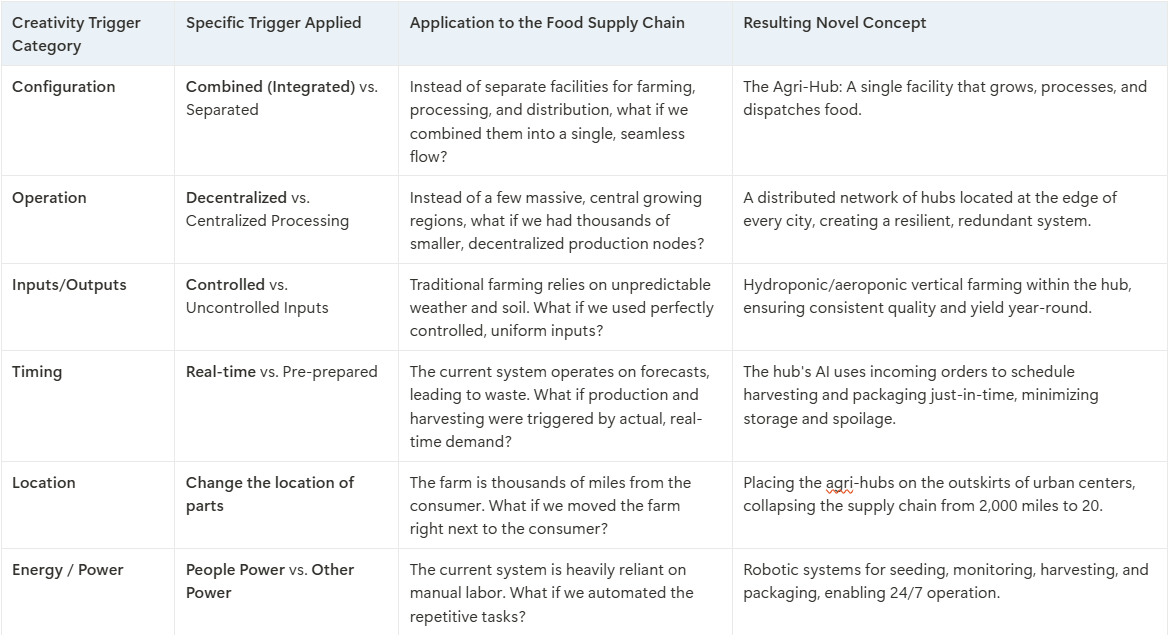

How do you arrive at a concept like this? By systematically challenging the assumptions of the current model using creativity triggers.

This systematic approach allows you to move beyond simple optimization and begin designing a fundamentally new and superior system.

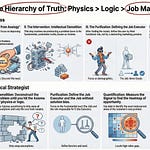

Part 3: Evaluation - Building an Uncopyable System with Doblin's 10 Types

A great idea is not enough. A venture-backed startup needs a durable competitive advantage—a moat. This is perhaps the biggest blind spot for many accelerator-bred companies. They build a product, but not a business.

Burnt's moat is shallow. It's based almost entirely on one of Doblin's 10 Types of Innovation: Product Performance. They are building a better piece of software, a more clever algorithm. While impressive, this is the easiest type of innovation for competitors to copy. What's to stop Amazon, with its immense logistics expertise and engineering talent, from building a similar or better "agentic OS" and bundling it with AWS? What's to stop a well-funded new competitor from poaching their talent and leapfrogging their tech?

Build a moat that can float a Ship. The perfect response to the Build & Ship evangelists

A truly deep moat is not a single wall; it's a series of interlocking defenses. It comes from layering multiple types of innovation across the entire business model.

Let's look at how the "agri-hub" concept could be architected into a deeply defensible business by strategically layering these innovations.

Configuration Innovations (The "Back Office" Moat)

This is the stuff competitors don't see, and it makes the business incredibly hard to replicate.

Profit Model: You don't sell SaaS subscriptions. That’s the old model. Instead, you create a value-share model. The agri-hub network takes a percentage of the money saved from eliminated waste, transportation, and intermediary markups. Your revenue is directly tied to the value you create for producers and consumers. This aligns incentives perfectly and makes you a partner, not a vendor.

Network: You're not just a tech company; you're a network orchestrator. You build a proprietary, three-sided network of technology partners (robotics, AI), real estate partners (who own and develop the hub locations), and food producers (who use the hub as their channel to market). The network effects here are powerful; each new participant adds value to all the others, creating a flywheel that's difficult for a new entrant to stop.

Structure: You structure the company to be asset-light. You don't own the farms or the delivery drones. You franchise the hub operating model and focus on developing the core technology, brand, and network standards. This allows for rapid, capital-efficient scaling while maintaining quality control.

Offering Innovations (The "Product" Moat)

This is the core product and the services around it.

Product Performance: This is the "agentic OS" at the heart of the whole system. It's the software that manages everything from crop growth cycles to robotic harvesting schedules to autonomous delivery routing. It's the brain.

Product System: You don't just offer one piece of software. You offer an integrated ecosystem of tools. Hub operators get a dashboard for managing their facility. Producers get demand-forecasting tools to help them decide what to grow. Consumers get a beautiful app for ordering ridiculously fresh food. These pieces all work together, locking users into your platform.

Experience Innovations (The "Customer-Facing" Moat)

This is how you create a brand and a customer relationship that transcends features.

Service: You offer unique, data-driven services that no traditional distributor can match. Imagine "Yield-as-a-Service," where your network's aggregate data provides hyper-accurate recommendations to farmers on what to grow next month for maximum profitability. This makes you an indispensable advisor.

Channel: You're not just improving a channel; you are creating a new channel. This model bypasses wholesalers, distributors, and traditional retailers entirely. It's a direct-to-consumer and direct-to-business channel for fresh food that is fundamentally faster, cheaper, and more resilient than any other.

Brand: You build a brand that stands for more than just logistics. It stands for freshness, sustainability, and community resilience. It's the story of "food grown 10 miles from your home, delivered within 2 hours of being picked." That's a narrative that a traditional logistics company can never credibly claim.

When you layer these 8 different types of innovation together, you create a complex, interlocking system. A competitor can't just copy your software; they have to replicate your entire business model—your profit model, your network partnerships, your service offerings, your channel. The cost and complexity of doing so create a truly formidable moat.

From Accelerating Features to Incubating Foundations

Let's circle back to where we started. Burnt is a smart company filled with smart people trying to solve a hard problem. But they are trapped by the prevailing assumptions of the industry they're trying to fix. They are building a better shovel when the real opportunity is to invent the excavator.

The journey we just took—deconstructing the problem to its physical axioms, reconstructing a solution around a core human job, and evaluating its defensibility as a complete system—is the kind of foundational strategic work that creates durable, category-defining companies.

This is the accelerator's blind spot.

In the frantic, three-month race for a polished demo day pitch and a slick MVP, this deep, foundational work is often skipped. The focus gravitates toward what can be built quickly: the feature, the app, the algorithm. The mandate from accelerators must evolve. The primary question shouldn't just be, "Can you build the tech?" It must be preceded by more fundamental questions:

Have you broken the problem down to its core, irreducible truths?

Do you truly understand the customer's Job-to-be-Done, or are you just optimizing a legacy task?

How will you build a system of innovation, not just a single product, to create a durable competitive advantage that can withstand the test of time and competition?

Answering these questions is the difference between building a feature and building the future. It's the difference between creating a clever optimization and architecting a new reality. And it's the kind of thinking that will produce the next generation of truly iconic companies.

Follow me on 𝕏: https://x.com/mikeboysen

If you'd like to see how I apply a higher level of abstraction to the front-end of innovation, please reach out. My availability is limited.

Mike Boysen - www.pjtbd.com

Why fail fast when you can succeed the first time?

Masterclass: https://pjtbd.com/mc

My Blog: https://jtbd.one

📆 Book an appointment: https://pjtbd.com/book-mike

Join our community: https://pjtbd.com/join